Originally published in Vanguard, April 1988 Print

Nietzsche, Nationalism and the National Front

By JOE PEARCE

IN Nietzsche - A True Perspective, published in the last issue of Vanguard, Dr. Henry Campbell sought to explain "some of Nietzsche's basic objectives and concepts" and to clarify "some of the misconceptions about Nietzsche". This being the article's professed purpose, there can be no objection whatever to its publication.

However, the publication of such an article begs a question which Nationalists in general, and the National Front in particular, can ill afford to answer wrongly.

To what extent are specific philosophical schools of thought relevant to Nationalism as an ideology and Nationalist organisations?

In order to answer such a question it becomes necessary to define a number of terms. Thus, 'ideology' is defined by the Oxford Illustrated Dictionary as a "scheme of ideas at basis of some political or economic theory or system". 'Philosophy', on the other hand, is defined by the same dictionary as the "love, study, or pursuit of wisdom or knowledge, especially that which deals with ultimate reality, or with the most general causes and principles of things".

Accepting the above as valid working definitions it becomes immediately apparent, therefore, that there is a definitively distinct difference betwen ideology on the one hand and philosophy on the other. Furthermore, it follows from this that Nationalism, as an ideology, is distinctly and definitely not a philosophy.

To be precise, Nationalism is defined by the Oxford Illustrated Dictionary as a "patriotic feeling, principle or efforts" or a "policy of national independence". Many Nationalists would doubtless develop that definition further, but Nationalism, is clearly not philosophical since its scope is both specific and limited, springing from natural patriotic feelings and manifesting itself in efforts towards a policy of national independence.

It is neither metaphysical nor esoteric in substance, dealing neither with ultimate reality nor with first principles and causes and it is readily accessible as an idea to the masses.

This being so, it becomes apparent immediately that Nationalism, as an ideology, has limitations in scope beyond which it logically can't trespass. Thus, in turn, makes it equally apparent that there is a need to map out the perimeter within which Nationalist ideology is encompassed.

To put in bluntly, Nationalist must be doctrinaire. It must start with its first principle of preserving the nation's existence and must build from that a comprehensive set of secondary principles which are, in themselves absolutely essential for the preservation of that first principle which is Nationalism's raison d'etre.

Indeed, the explanation and exposition of those secondary principles - racial, national, social, economic and ecological - which are necessary for the attainment and maintenance of Nationalism's first principle was my intention in writing Nationalist Doctrine.

Nonetheless, the motivation for my writing of Nationalist Doctrine had precious little to do with the need to delineate the difference between philosophy and Nationalist ideology. On the contrary, its purpose was to illustrate the inadequacy of supporting a sundry range of separate policies without recourse to a doctrinaire ideology which would give such policies the acid test of being either compatible or incompatible with the survival of the nation.

Nationalist ideology, therefore, serves to root out those policies which are incompatible with its first principles. To put it plainly, it is a safeguard against the intellectual threat from below, the tendency of the unknowledgeable to profess mutually inconsistent views.

However, and returning to our central theme, ideology is equally a safeguard against the intellectual threat from above, the tendency and temptation of intellectuals, psuedo- and otherwise, to impose their own philosophical beliefs upon others.

The point always to be remembered, though all too often forgotten, is that Nationalism is a political ideology and not, emphatically not, a metaphysical philosophy. Of course, such an affirmation doesn't preclude Nationalists from holding philosophical views. Indeed, just as individual political beliefs can be either compatible or incompatible with Nationalism, so individual philosophical beliefs can be either compatible or incompatible with Nationalism.

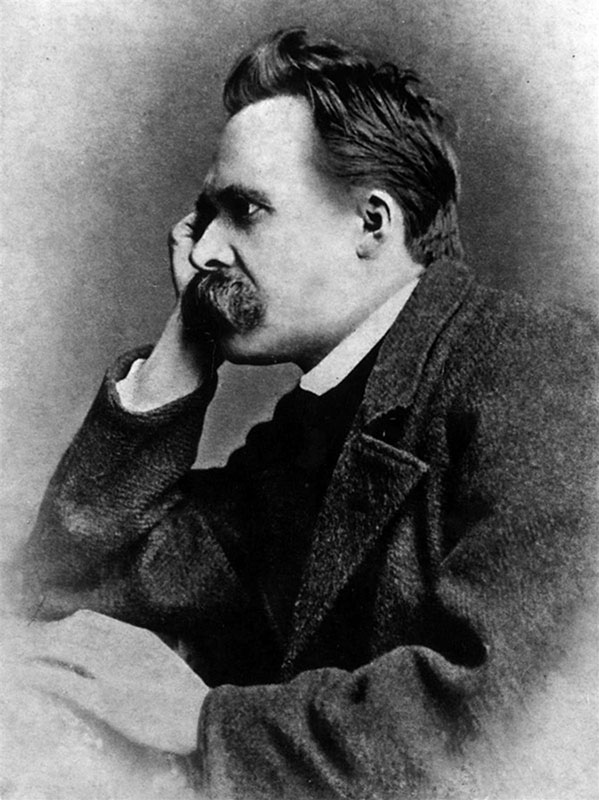

Freiderich Nietzsche

Thus Dr. Henry Campbell would doubtless argue that Nietzscheanism is not only compatible with Nationalism but is a powerful ally of Nationalist ideological tenets.

Thus also a Christian Nationalist might argue that Thomism, the philosophy expounded and explained by St. Thomas Aquinas, is not only compatible with, but supportive of, Nationalist ideology. On the other hand, few Nationalists, if any, would dispute that the philosophy of Marxism - assuming the views of Karl Marx warrant a philosophical status - is incompatible with Nationalism.

However, and here is the crux of the matter, whereas individual policies are contained by an ideology, an ideology is contained by a philosophy; or, to put it another way, philosophy cannot be part of Nationalism even though Nationalism may conceivably be part of a philosophy.

In essence, therefore, no political ideology has any mandate or logical justification for going beyond its raison d'etre. In the case of Nationalism, that raison d'etre is the survival and well-being of the nation and Nationalist ideology is the set of interdependent beliefs essential for its attainment.

Many may argue, assuming they have endeavoured to read thus far, that all the above is extremely abstract, esoteric and irrelevant. Indeed it is both abstract and esoteric, but it is most definitely not irrelevant. In fact, it contains some very important and practical lessons for Nationalist organisations like the National Front.

The NF was formed in 1967 to combat the various internationalist policies of successive Tory and Labour governments.

The NF's membership consisted of former Labour and Conservative voters alike, transcending social classes and erstwhile political divisions. The NF was aptly named. It was indeed a national front against all that threatened Britain's independence and identity.

Inevitably, however, problems arose from the Party's lack of any coherent ideology. Many members, although united in their opposition to immigration, the Common Market and other overtly internationalist institutions, still adhered to the less obvious but inherent internationalism of multinational capitalism.

Not being armed with any ideology to point out the illogical nature of their opinions, these NF members fell back on the laissez-faire principles of economics which had created the multinational monsters which were doing more than anything to endanger national freedom.

Consequently, the NF succumbed to what is described above as the intellectual threat from below, the tendency of the unknowledgeable to profess mutually inconsistent views. The result of this, during the early 1980's, was much soul searching with the result that many returned to the right-wing ranks of the Conservative Party from whence they had come originally.

Nonetheless, every cloud has a silver lining and many Nationalists set about ensuring that the threat from below was confronted and conquered by the development of a logically consistent ideology. Indeed, this ideological development is one area where there has been indisputable progress.

Now, however, unless the problem is nipped in the bud, the intellectual threat from above looms menacingly on the horizon. If the Party fails to distinguish between ideology and philosophy and neglects to lay down appropriate demarcation lines, a blind alley beckons the movement out of which it may never emerge.

What is that blind alley? It is the blind alley of philosophical totalitarianism which can best be gauged by taking some caricatured and hypothetical examples. For instance, if the Nietzscheans imposed their philosophical beliefs upon the Party, it must, of necessity, alienate all Christians within the movement since Nietzscheanism is avowedly atheist.

Once this were done, the movement would be up the blind alley of obscurantism, excluding millions of patriotic yet religious Britons from its ranks. Such a movement may be called a Nietzschean Front but it wouldn't be a national front.

Going to the other extreme, if a group of militant Christians imposed their philosophical beliefs upon the Party, it must, of necessity, alienate all those who fail to share their religious fervour. Atheists and agnostics alike would be excluded from such a Party. It may like to call itself the Legion of Michael the Archangel or some other grandiose title, but it couldn't with any credibility call itself a national front.

Sceptics may sneer that such examples are not rooted in reality, yet only recently divisions were wrought in the Party by those who sought to impose philosophical dogmas upon the movement. Thankfully those individuals have now purged themselves from the NF's ranks and are happily following obscure tangents which make them progressively more irrelevant to the general public without whose support they are powerless.

No, the intellectual threat from above is a very real one which has already reared its ugly head once. Only by understanding the demarcation lines between philosophy and ideology can that problem be overcome.

The opposition to internationalism must never be a front for Nietzscheans alone or Christians alone. It must never be the preserve of any single philosophical school. On the contrary, it must be a front for all members of the Nation. It must be a movement worthy of the name National Front.