Originally published in Vanguard, May 1989 Print

THE COMING OF THE ANGLO-SAXONS TO ENGLAND

STEVE BRADY

(The first part of this article appeared in Vanguard, issue 24, and is included in this archive)

HOWEVER SUPERFICIAL the genetic contribution of later waves of incomers, when we reach the Anglo-Saxon incursion, the "coming of the English to England", it seems beyond doubt, surely, that this time the Immigrants must have prevailed utterly, at least in that large part of Britain to which they even gave their name? Spirited native British resistance, which may well have been led by the historical Arthur, King or otherwise, might hold back for a time but could not stem the Saxon tide.

A tide which must have surely swept all before it not just in terms of speech, customs, way of life, law and government but also blood and race? Or did it? Are the English really 'Sassenachs', - Saxons racially distinct from the 'Celts' and the rest of Britain? It is an argument which has buttressed Irish Republicanism and other brands of 'Celtic' separatism down the ages. But is it true?

Well, when we come down to the hard facts of the actual concrete numbers involved in this supposed 'racial transformation' of England a startingly different picture emerges. Historians now consider that the total number of Anglo-Saxons who came to Britain was "not more than 50-100,000" - see for example Lloyd and Jennifer Laing Anglo-Saxon England. Paladin, 1982, p.62, or Leslie Alcock, Arthur's Britain: History and Archaeology AD 367-634, Penguin, 1973, p331.

The native 'Romano-British' population of England at the close of the Roman period is universally agreed to have been well over a million, although a series of plagues in the 6th Century may have reduced it somewhat, especially in the cities and towns of the South-East. But even if the native population had been halved by plague and famine - and not even the Black Death managed to achieve this - the native Britons still outnumbered their Saxon 'supplanters' by five to one!

RULING MINORITY

Hardly surprisingly, therefore, the evidence shows that the Anglo-Saxons, like the Normans after them albeit on a much larger scale, essentially took over as a ruling minority, although unlike the Normans they included a substantial proportion of yeoman farmers as well as warrior lords. But even these farmers seem seldom to have actually displaced the native peasantry. As M.G. Welsh found in a detailed study. Late Romans and Saxons in Sussex Britannia ii, 1971, p.232, "the areas taken by the new settlers were precisely those left vacant or underused by the Roman-British population". As Dr. Stephen Johnson puts it, summarising a growing body of evidence from all over the Saxon settled area, "there are many indictations that the earliest Saxon arrivals settled on the fringes of Roman villa outfield systems, or on marginal land between two neighbourhoods. Whether this means Roman 'control' of Saxon settlement in an organised sense, or whether it means that the Romano-Britons, already in command of the best agricultural land, were not likely to be easily shaken off by a handful of incoming settlers, is a matter for debate. It is more likely that the known Saxon villages were placed on marginal land because the incoming numbers were relatively few, and that they lived under the tenurial control of the existing landowners. In places they may have established a communal modus vivendi" (Later Roman Britain, Paladin, 1982).

Dr Johnson also points out that there is growing evidence of continuity of parish and estate boundaries from later Roman into Saxon times, implying a degree of legality about the transfer of land title, or at least of local knowledge, sharply at variance with the popular notion of savage pagan hordes of Saxons looting, burning, raping, killing and seizing the land whiist the native 'Celts' ran for the hills.

Battles there certainly were, as Saxon war-leaders fought the British rulers for the right to govern the land and live off the produce of, rather than exterminate, its ordinary people. The end result in one area from which we have clear evidence, North-eastern England, is summed up by Leslie Alcock, Reader in Archaeology at University College Cardiff, thus: "The conclusion is inescapable that a very small and largely aristocratic Anglian element ruled over a predominantly British population" (Arthur's Britain, op.cit., p331)

The proportion of incomers to natives doubtless varied from one area to another, but it is now generally agreed that everywhere the invaders were simply not numerous enough to physically dispossess the natives of the land, even if they had wished to thus dispossess themselves of such a source of useful agricultural labour and produce. Over much of England, the natives might henceforth hold the land in bondage, but hold it they did, nonetheless.

Certainly, the invading minority imposed their language utterly on the native majority, as the decendents of both were similarly to do in Ireland, Scotland, Wales and Cornwall, simply because, one the last native resistance had been smashed, as in England it had been by the mid-7th Century, it was the tongue of power, prestige, commerce and government from the village level up, which anyone who did not wish to brand himself an ignorant bumpkin had to master and use. Yet even so, our rivers for example mostly kept their old English names - Trent, Derwent, Ouse, the sundry Avons (from the Celtic word for 'river' - afon in modern Welsh) and the pre-Celtic name Thames.

As did the Chilterns, hills in the Home Counties far from the Celtic fringe and the Pennines, the backbone of England. And, furthest of all from that northern and western fringe, the county of Kent, which Caesar in 55BC found populated by the Cantiaci, and the city of Canterbury (which acquired the Anglo-Saxon suffix byrig - fortified settlement).

British too are the names of towns in the heartland of England such as Cannock, in the West Midlands and Liss, Hampshire (from British tisso, in modern Welsh llys, site of the King's court)

The invaders themselves bestowed names on places attesting to their continued habitation by the natives: many of the place names incorporating Wal - such as Walton and Walsham derive it from the Saxon word wealh applied to native Britons. It orginally meant foreigner - in their owh country, for that indeed has happened before now - and later serf - which might happen again unless we are careful! - before ending up in modern English as 'Welsh'.

There are also Bretton - Britons' town, and Cumberworth, from cumbrogi, in modern Welsh Cymry, 'citizens', from Latin cives, the natives' word for themselves. Camberwell in London may well incorporate both words for Briton.

And of course many larger towns of the period kept their old names, like Leeds and London. Some had Saxon words tacked on (often ceaster. from Latin caster, 'military camp'), as in Manchester, Rochester and Doncaster (incorporating the name of the Celtic fertility Goddess, Don).

Mere survival of place names is actually less significant - North America is similarly littered with aboriginal tags like Mississippi and Chicago which clearly do not reflect an overwhelming Red Indian contribution to the U.S. gene pool. But we don't find any 'Injunstowns' or 'Redmanvilles' or 'Cheyanntons', as we do Waltons and Brettons, attesting to continuing large-scale native presence, nor did Red Indian tribal boundaries persist, as Romano-British parish boundaries did here.

CONTEMPORARY EVIDENCE

The question must, however, surely be settled when, on top of population and place names evidence, we encounter contemporary documentary evidence, attesting to the presence of substantial numbers of Welsh in Anglo-Saxon England.

For example, the laws of King Ine of Wessex, dating to the late 7th Century when Saxon power was firmly established, refer repeatedly to his 'Welsh' subjects. Although legally inferior to the Saxon ruling class, by no means all 'Welshmen' were peasants: a number of 'Welsh' nobles held 'five hides of land', no mean wealth in Ine's Wessex, and some 'Welshmen' of Wessex held royal office and rode abroad upon the King's business.

500 years later, the Wessex 'Welsh' were still clearly identifiably there: when Henry I in the 12th Century issued a law code for religion, it too contained repeated special reference to 'Welsh' inhabitants as a distinct class, if now only as 'Welsh bondsmen', the nobles having presumably merged into Saxon nobility.

Detail of a fanciful Victorian illustration of Hereward the Wake fighting the Normans

Perhaps they still spoke their own language - as we know the fenlanders around Cambridge still spoke Celtic in the 11th Century, when they aided the English Resistance fighter Hereward the Wake fight another invading minority (see John Morris, Senior lecturer in Ancient History, University College London, The Age of Arthur: A History of the British Isles from 350 to 650, Weidenfeld and Nicholson, 1975). Kent too had its laws for 'Welsh' laet, and as late as the 10th Century York had a legally recognised class of Wallerwents.

Nor were the Saxon invaders themselves wholly foreign to these shores. The very founder of the Royal House of Wessex, from whom Alfred the Great and subsequent Kings of the English sprang, Cedric, himself had a 'Welsh' name - Caradoc, the same name as the earlier hero of native resistance the Romans called 'Caractacus'.

Some generations later, his successor as King of Wessex from 685-688 also had a Celtic name, Cadwallon, or Caedwalla as the Saxon scribes spelt it. As had his brother Mul, and grandfather Codda. As late as the 8th Century, 200 years after the Saxons came, Wessex still had an Ealdorman Conbran and an Abbot Catwal (Cadwallon, again). In Northumbria, the 'Anglian' bard Caedmon had a 'Welsh' name. In Kent, a royal officer with the name Dunwald (as in Scots Donald) owned a substantial slice of Canterbury in the 8th Century, and in 787 the Kentish ambassador to Mercia bore the Celtic name Maelgwn, Latinised to Malvinus.

Ultimately decisive in answering any such question of the relative contributions of populations to national gene pools - if currently unfashionable for wholly unscientific reasons - is the hard evidence of physical anthropology, read from skulls and bones which, unlike chronicles and their scribes, cannot lie or distort the truth.

Here we bow to the authority of Dr. John Baker, F.R.S., of Oxford University, (Race, Oxford University Press, 1974, p.266): "Physical anthropologists, relying on evidence provided by the skulls of ancient and modern times, consider that the descendents of Iron Age people of Romano-British times continued to occupy the country during the period of Anglo-Saxon domination, and were so far from being driven away or exterminated that it might almost be said that it was they who eventually absorbed the Anglo-Saxons, while adopting the language of their conquerors."

'RACIST' EVIDENCE

Even the multiracialist TV pop historian Michael Wood, who would no doubt shudder to touch such 'racist' evidence with a barge-pole, concedes the point thus: "Whatever the Anglo-Saxons thought they were in the seventh century, we may be sure that their racial identity was neither Germanic nor Celtic, but a fusion of the two". (Michael Wood, Domesday: A Search for the Roots of England, BBC Publications, p.80).

The 5th Century "extermination of the Britons", like other more recent 'Holocausts', evaporates on close expert examination as a phantasmagorical foundation of propaganda and self-justificatory hype: in this case the bombastic exaggerations of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, the ethno-masochistic rantings of the Sixth Century sermoniser Gildas, and the vague speculations of the Anglo-Saxon cleric Bede, writing 300 years later.

So, as with the later arrival of the Danes and Normans, the truth of the "coming of the English to England" is again not one of 'conquest by immigration', of the native people being swamped and driven out by foreigners. That is reserved for our own, more 'enlightened' times. Instead it is but the washing of another superficial wave across the surface of very deep racial water, the gene pool of our people, the wellspring of our nationhood.

The "English" are no more "Saxons" because they adopted the language of an Anglo Saxon-speaking conquering minority than the Southern Irish are because they did exactly the same. Indeed, as we shall see in the final instalment of this series, the English are ethnically as least as "Celtic" as the Irish and more so than either the Scots or Welsh!

The 'Sassenach' smear, like all the other efforts to justify the division and fragmentation of the British nation and people which underlie Irish Republicanism, 'Celtic' separatism and other attempts to Balkanize Britain, is an historically baseless propagandist lie. The British are, at root, one people, older by far than either Saxon or Celt. Who that people are, we shall discover in our next instalment.

ROMAN INVASION

But first we must deal with the earliest invasion of Britain in historic times, that of the Romans. This involved the largest, most centrally organised single invasion of our islands in all our history prior to the Afro-Asian invasion of modern times. Twenty thousand combat troops of four legions, plus the same number of auxiliaries, landed in Southern England in 43 AD, at the command of the somewhat underrated Emperor Claudius. For four centuries, and for the only time in our nation's history until we joined the Common Market, much of our land was governed from far outwith our borders, subject to an alien power, its laws, language and culture.

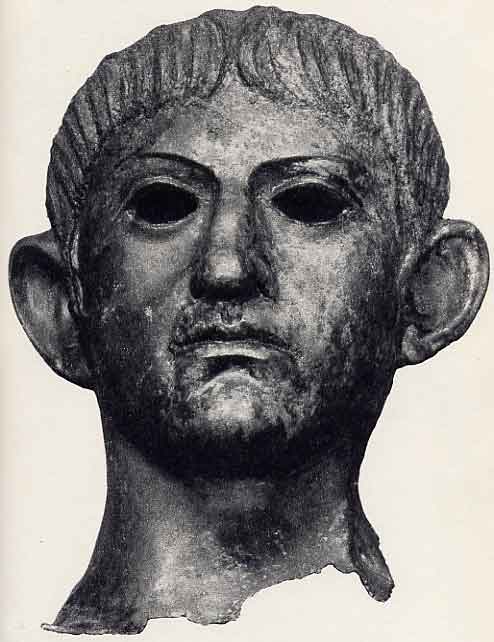

The Emperor Claudius

Yet Rome's influence was largely superficial. Culturally, even after 400 years, Roman speech, manners, dress and civilization barely extended beyond the 'Civil Zone' of the Imperial administration of Britain, the area of South-Eastern England and the southern half of the Midlands. As Dr. Lloyd Laing, Senior Lecturer in Medieval Archaeology at Liverpool University puts it in his Celtic Britain (Paladin, 1981, p. 141), "Outside the Roman areas, in the North, particularly, the Empire had little effect on the native population. The archaeological material shows no break - pottery, houses and general way of life were unchanged. Border areas seem to have been affected by Roman doctrine which permeated into the Dark Ages, but apart from the physical barrier of Hadrian's Wall which probably prevented the traditional movement of stock, Celts were still Celts in the North. In areas where the Romans found little politically or economically to exploit (such as Wales or Cornwall) Romanization of everyday life was rare, imports sparse and only the ethos of Rome lived on into the Dark Ages."

In a British rebellion against Roman rule the head of the Emperor Claudius was removed, as a trophy, from his statue in Colchester in AD61.

The true thiness of the Roman veneer even in the south-eastern British heartland of Imperial sway can be gauged from the fact that, alone of Rome's provinces, even after four centuries Britain kept her native speech and ancient Celtic tribal organisation, which promptly re-appeared on Rome's withdrawal. Not for us, as for Gaul and Hispania, some debased gutter dialect of vulgar squaddies' camp Latin: we came out of the Roman Empire speaking the same Celtic tongue more or less, as we went in, an ancient tongue which, though rightfully the common heritage of all Britons, still survives in Wales, and Brittany, and is being revived in Cornwall.

Indeed, as the fourth century temple of Celtic God Nodens at Lydney, Gloucestershire, reveals, our ancestral faith also lasted long before it was stifled by 'the god of the nails from Rome' as Chesterton put it. Only in the cities and larger towns of the South did Rome sink any deep cultural roots, and they were the worst afflicted by the plagues of the 6th century.

If the cultural impact of Rome was superficial, the genetic effect, which as we have seen is generally much less than the cultural one, must have been minimal. As it was. Rome kept, for most of her time here, three legions, around 18,000 men, stationed in Britain. As the years went by, much of these, like the Imperial civil administration here, would have been drawn from the native population.

However, we do know that some Romans, and even the Syrians and Egyptians and other dross with which the later Empire was busy rotting its gene pool, did find their way here. But in a population estimated as between one and two million, a few thousand aliens would have been simply swallowed up. Britain was sufficiently remote to be spared the mass immigration, the 'Orontes flowing into the Tiber' as Juvenal put it, which ruined Rome herself.

Rome gave us a concept of citizenship and nationhood, the idea of Britannia as an identifiable whole worth fighting for, of her people as citizens or countrymen - cives. A national ideal which inspired a heroic and above all national, not tribal, resistance to the Saxon invader of which British National Resistance Arthur became a legendary symbol.

But genetically, even in England, Rome left barely a mark, and in Wales, Scotland, and especially Ulster and Ireland, not even that. Norman, Viking and Saxon most of us can claim amongst our forebears, albeit they are none of them pre-eminent in our ancestry. But the blood of the Caesars runs thinly, if at all, in our genetic veins.

ANCESTRY

So Roman and Saxon, like Dane and Norman, make up only a small share of our ancestry. So who makes up the bulk of it? As Baker (op. cit., p.266) says, "the present day population of England and much of Scotland is to a very considerable extent derived from the Celtae and Belgae of the Iron Age".

But who were they? And were even they our true forebears? When Julius Caesar, reconnoitred Britain for Rome in 55-54 B.C., he reported (De Bello Gallico, Book V: 12) "The interior part of Britain is inhabited by tribes declared in their own tradition to be indigenous to the island".

It is in search of these indigenous peoples, back into the mists before history, to the Celts and beyond, that we shall quest in the third and final article in this series as we seek not only to nail the lie of a "nation of immigrants" but to find out who we, the British people, really are...

(The final part of this article appeared in Vanguard, issue 26, and is included in this archive.)